In this article, Epic Leadership Development team member Brian Virtue (along with two colleagues from Destino and Impact Movements) writes about five “postures,” or heart attitudes, that majority culture individuals often assume towards ethnic minority ministry. This resource provides clarity and wisdom on topics that are infrequently discussed, and will inspire you to reconsider your role in God’s mission and the ethnic story.

When you hear the phrase “Ethnic Minority Ministry” or “Ethnic Ministry” what is the first thing that comes to mind?

What thoughts and feelings surface when the topic of Ethnic Minority Ministry is broached?

This article is written by three Caucasians, all members of the majority culture, who have personally wrestled with what it means for Caucasians to minister in ethnic minority contexts. We have each served for several years now in different ethnic minority ministries that exist at the periphery of a large and mostly Caucasian ministry organization. Eric has ministered through the Destino Movement, Brian through the Epic Movement, and Tommy through the Impact Movement. Destino, Epic, and Impact are Campus Crusade for Christ’s ministries through Latino/Hispanics, Asian-Americans, and African-Americans respectively.

We all agree that the relationships we’ve made within ethnic minority communities have deeply changed us as people, leaders, and ministers. We’ve seen our own lives enriched through our learning to serve communities different from our own.

All those in ministry have a response of some kind to ethnic ministry. In fact, whatever our background or previous ministry experience might have been, we all lead out of some kind of orientation to ethnic ministry. This orientation, this posture if you will, typically informs what we value, how we make decisions, and how we navigate the growing complexity and diversity of our ministry landscape.

Through our own experiences, we’ve become aware of several different postures towards the idea of ethnic minority ministry – some of which we’ve held at different points ourselves on our own cross-cultural ministry journeys. We are continuing to learn through making mistakes and having our misconceptions challenged.

Why are we focusing on “postures?” We believe that a posture reflects not just a mental approach or paradigm, but a holistic approach that includes both our hearts and minds.

While the ministry landscape and demographics of North America have changed dramatically, the response of those within the majority culture has sometimes been one of confusion, insecurity, and resistance. However, for a church or ministry to effectively minister to all of those within the scope of its ministry, those ministering must examine their posture towards ethnic ministry and consider if it is marked by love and servanthood.

The five postures we have consistently experienced and identified are (1) unfamiliar and unaware, (2) duty and obligation, (3) charity, (4) unity as togetherness, and (5) advocacy in partnership. Our aim is not to provide a thorough apologetic for crossing cultures, but to describe postures towards ethnic ministry commonly held by majority culture leaders and ministers. We hope to provide common language for cross-cultural development amidst majority and minority dynamics.

Our goal is not to label where any one person might be at in his or her posture towards ethnic ministry. We acknowledge that we ourselves cannot represent the ethnic minority story in full because it is not our own story. Our desire is to paint a picture of the spectrum that we have observed as we have served with ethnic minorities. These postures are not linear in nature and are not meant to convey a sequential journey of development from one posture to the next.

All five postures exist at every level within a ministry. Ministry experience or organizational authority does not directly correlate with healthy postures or partnering with ethnic ministry. International cross-cultural experience is also not necessarily connected to a healthy partnering within ethnic ministry contexts. Those with significant international ministry experience usually grasp cultural differences well, but they may sometimes lack understanding in majority – minority dynamics and the ways in which power works in society and how ethnic minority identity is shaped.

No matter what the level of ministry experience, we value the process of one’s development in understanding the ethnic ministry story over time. We also recognize the necessity for a sense of reflective urgency about our own posture. There is a great need for leaders who both can see and enter into the ethnic minority story.

You might not identify with one posture over another. Perhaps two or three will together capture your posture. That’s okay. Our hope is that you pay attention to what this surfaces within you and make an honest assessment of your own posture towards ethnic minority ministry. We pray that you’ll take the time to reflect on what God might be encouraging you to consider in your own development and leadership.

Posture #1: Unfamiliar and Unaware

The first posture that we have observed is best described as a general unawareness of the ethnic minority world. This is often grounded in the simple reality of unfamiliarity. Maybe you have always lived in a part of the country where you rarely interact with those outside of your own culture. You may not have personally wrestled with how our ministry needs to respond to the increasing ethnic diversity of our country. Maybe you find yourself checking out when the topic of ethnic ministry comes up because you don’t see its relevance to your life and ministry.

Sometimes we may believe that we are more familiar with ethnic ministry than we really are. Experiencing multiple trainings and exhortations can result in us feeling like we are informed on what is needed for ethnic ministry. Or maybe you grew up with ethnically diverse friendships. You are comfortable with diversity, but maybe upon reflection you realize that you don’t know as much as you thought you did. This was the case for us. For a long time, we each felt comfortable in diverse friendships, but we were not yet familiar with the stories that shaped who our friends were.

It’s important to recognize that being aware of the need for ethnic ministry or even being comfortable around ethnic diversity is not the same as being familiar with the reality of ethnic minorities. Familiarity is an intimate, personal knowing of people living the ethnic minority story, to the point where you start to see the world through the eyes of another culture. One can be very knowledgeable of the statistical and strategic objectives, but very unfamiliar with the needs of the people that the strategy serves.

Being unaware to the reality of ethnic ministry is not always a reflection of your heart. But, if you find yourself checking out when ethnic ministry comes up, consider the changing world and the opportunities to join something that will be an increasing part of life and ministry in North America. You are standing at the gates of a whole new world spiritually and socially. God longs to expand your view of Him and your heart for those that are different from you.

Posture #2: Duty or Obligation

The words “duty” and “obligation” can convey a lack of inspiration, a lack of heartfelt motivation, and a lack of enthusiasm for engaging in the challenge at hand. But these terms can also describe the posture of someone torn between what feels natural and comfortable and what they are being asked to do.

Ministry leaders know today that the scope of their ministry includes mobilizing efforts towards ethnic minority communities. There have been abundant reports about shifting demographics, all of which paint an urgent picture. Yet while statistics can point to a need, they cannot orchestrate intrinsic motivation or passion for being part of a solution. Statistics without story usually create guilt and pressure.

You might see the great need for cross-cultural ministry even within your own scope of ministry. On some level you do care about the spiritual needs of ethnic minorities. So maybe you dip your toes into ethnic ministry from time to time. But you’re torn. You love what you do day in and day out. It feels comfortable and familiar. Or maybe you already feel overwhelmed with the current scope and responsibilities of your ministry. Wading deeper into the waters of ethnic ministry may feel like an additional project that you can’t take on right now.

What might it look like if your heart came alive in response to new knowledge of and familiarity with the story of a particular ethnic group? Would you consider praying that God would give you a passion, maybe the kind of passion that Jewish Paul had for the Gentiles, for a specific ethnic group? Can you prioritize spending time in at least one community that God can use to increase your vision and passion?

If your heart is open for God to take you to a new place through another culture, you may see your entire paradigm of ministry transformed and energized! But we must be willing to move beyond statistics and enter into new stories in fresh and deeper ways.

Posture #3: Charity

A third posture many majority culture ministers have towards ethnic minority ministry is that of giving to charity. This posture is not always obvious, but it is probably one of the most common. Perhaps you see the desperate landscape in which the numbers of laborers are minuscule compared to the growing demographics of different communities. You know something needs to be done, yet you hesitate to dramatically alter what you are currently doing for the sake of being a part of that solution.

Perhaps you’ve thought, “When our ministry gets big or healthy enough, then we’ll then have the resources to do more ethnic ministry. We just don’t have the manpower right now.” Maybe you have adopted a “tithing” approach where you intentionally allocate a small percentage of your time or resources toward ethnic ministry.

We would wholeheartedly affirm that in principle, doing something (usually) is better than doing nothing. But consider the ethnic minority story, a story which exists mostly on the fringes of society and privilege. It consistently battles the challenges of marginalization and feeling “one down” in society. In that context, would expressions of help out of a posture of charity truly result in transforming and redemptive interactions and relationships?

A charity posture exudes the “we have the answers that you need” mentality and reinforces the power disparity, which can actually reinforce pain as opposed to contribute towards healing. Charity often serves our own motives rather than truly serving and empowering others. A charity posture results in interactions that reinforce the feeling that ethnic minority ministry is a burden, afterthought, or second-class to the “main” ministry.

On the surface, charity can feel like advocacy. The critical difference is the motivation for doing ethnic ministry. It becomes charity when it is pursued out of a desire to accomplish our own agenda, albeit on a broader scale. Moving beyond charity to advocacy involves building relationships. A charitable posture is a one-sided vision for us to give (for example, of our time and resources). On the other hand, a relationship based advocacy is rooted in mutual learning and respect where both parties work together to give and receive.

If you find yourself seeing ethnic ministry as a charity to be helped, what if you approached ethnic minority leaders from a position of learner or servant, acknowledging them as experts in their own right? Imagine the transformation that could take place both personally and corporately if you moved from an attitude from helping from above to partnering together?

Posture #4: Unity As Togetherness

We want to be clear – unity within the Body of Christ is vital and necessary. Yet efforts towards unity sometimes can lead to uniformity. Without experiences with other cultures or doing critical reflection on our own cultural lenses we can begin to live like fish in water, not even realizing the water is there because our own cultural lens is all we know. As a result our idea of unity looks more like sameness or conformity. Our vision of unity can reflect what feels “normal” to us.

It’s easier for majority culture leaders to assume that unity includes sameness. This is because if everyone did everything the same way, majority culture members would not have to radically adapt, by the very nature of majority and minority dynamics. So the posture of “unity” that resists contextualized efforts is problematic for ethnic ministry. While this is not the arena to fully explore the theological or philosophical issues involved in contextualization and unity in multi-ethnic contexts, it is important to recognize that it is a false hope to believe that problems will be solved just by everyone just “putting Jesus first” and being together all the time.

Clearly, if our system or philosophy merely maintains the status quo, while keeping other groups on the margins, then we cannot adequately minister in love to ethnic minority communities. Our challenge is to expand our understanding of unity to include ethical considerations and reflections on the truth of where honor is truly being given in how we try to come together. We must pursue unity and diversity without losing one to the other – even if that might never be fully attainable in this lifetime.

But there’s an opportunity to develop a posture that moves us away from solving complexity through conformity and towards making space for people to emerge both spiritually and as leaders. Can you imagine what it might look like if we shifted our hope towards fostering partnerships that seek to honor and respect differences instead of minimizing or eliminating them?

For the three of us, our experience of ministry has expanded and effectiveness increased through relating to a more diverse group of people. As we’ve begun to appreciate and not feel like we need to “fix” the differences that we see in people, our own contribution to the kingdom has expanded whether it’s in a new culture or even our home culture.

Posture #5: Advocacy in Partnership

If you’re a member of the majority culture you have an incredible opportunity to steward your cultural power and status for the sake of healing and a redemptive future! But we as Caucasians can struggle to enter into the ethnic minority story because we might not know how we will be received. We may even distance ourselves from that story due to guilt or shame connected to past abuses of power. Or, we may feel defensiveness about the role of the majority culture in the ethnic minority experience.

But amidst all of the challenges, pain, and confusion that comes with crossing cultures in minority contexts, there is a role for Caucasians in the ethnic minority story – a different role than what has often been experienced in society and in many ministry efforts.

As Caucasians, we carry with us the capacity to reinforce much of the pain that ethnic minorities have experienced and absorbed both in their lifetimes and through generations of systemic marginalization. We can’t escape the larger story of which we are all connected. But when we as Caucasians begin to relate to ethnic minority communities in ways that bring honor, rather than take it away (albeit often unknowingly), there are great opportunities to open doors for healing, reconciliation, and empowerment.

We live in a culture in which we like to fix things quickly and avoid pain. If we enter into the world of ethnic minorities without being willing to feel the discomfort of our differences, then we will never see the world through the eyes of other cultures. If we never feel the pain embedded within that a particular culture’s history, then we will not be able to genuinely identify with them. Advocacy in partnership includes humility and learning. It means choosing to suffer with people out of love for what God wants to do in and through them and being willing to learn from them in return.

We think most ethnic ministry is done with good intentions. But not all seek to partner in ways in which there is mutual blessing and dignity. We cannot partner in ethnic ministry from a position of “above.” We can fight for people and influence them from above, but we can’t really partner with others in a redemptive and honoring way without fostering mutuality and dignity.

The posture of “advocacy in partnership” is an expression of true, adult partnering between the majority and minority cultures. This is something different than starting from above. It is different from helping struggling ministries get off the ground. It’s different from trying to “reach” or extend our influence into new communities because we will bless them through what we have to offer. Advocacy in partnership is more than just telling our story with an ethnic face. It is realizing that other stories exist, choosing to learn them, and identifying with them for their benefit.

Advocacy is something we can all do when we have power that others are unable to access. Serving and leading in ethnic minority ministries has increasingly shown us the power that we both often have as white, male leaders. We continue to learn new ways in which we underestimate the social power assigned to us in multi-ethnic settings. Majority culture leaders need to know this – we greatly underestimate the social power often assigned to us in multi-ethnic or dominant culture contexts. Even if you don’t think you have it, it’s there. If we fail to recognize this dynamic, we will not be able to see the ways in which we might be reinforcing the pain of the past, even through we may be well-intentioned.

Yet there is room for great hope! We are continuing to learn that when we use that power and status to serve and uplift others, we build trust and deepen relationships. Through serving alongside our ethnic brothers and sisters in humility, we can see God redeem much of that dark history. We can break through stereotypes and pain to be part of something beautiful and empowering. We can be a part of God’s restorative work of affirming people’s stories and drawing out their God given strengths and contributions.

To what end?

When we consider the mission of the church, we must recognize that there is always a power gap in any multi-ethnic community between the majority and the minority groups. Some people have more power to enact change than others. Given this power disparity, can we truly be agents of hope to the marginalized without purposely seeking to empower them? Advocacy in the context of partnering means putting those privileges we have been given by God’s grace to work on behalf of those whose stories are consistently silenced or ignored.

Partnering with or serving in ethnic ministry requires identifying with and seeing the world more through the lens of their culture and story. It leads us to change the way we perceive the world as we encounter and learn from other perspectives.

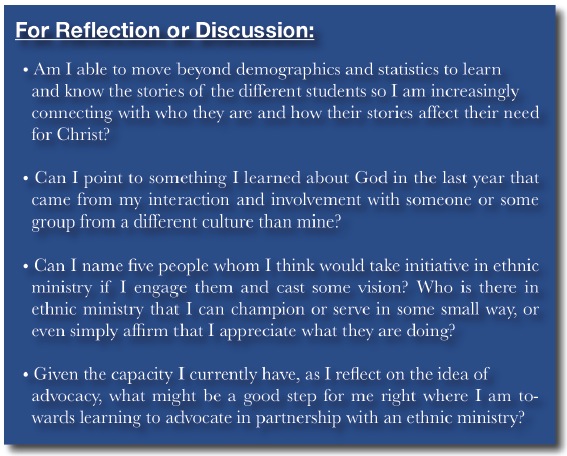

The challenge for us majority culture leaders is our willingness to experience change – both on a heart level, in how we like to relate to others, and in how we like to work. Incarnating the gospel amidst diverse communities means that we need to be willing to die to former attitudes, postures, and even insufficient ministry paradigms and methodologies.

But as in life with God, dying to old ways can open the door for new life. As we follow Christ, we experience the process of having our own stories expanded and deepened as God reveals more about ourselves, about Himself, and about the world.

The crucial questions become, “Are we willing to have our stories change or expand and have our hearts enlarged? Are we willing to put ourselves in positions in which we can shape other stories in redemptive ways and where we invite others who are different to shape our story as well? We have all inherited a story that is fallen and in which injustice abounds. What might it look like if we opened ourselves up to the possibility that God wants to use us to help rewrite a new story that includes and affirms all peoples?

God is at work rewriting stories throughout the world. He’s using a diverse body to accomplish His mission. For God’s kingdom, it matters that we are moving towards the marginalized and it matters how we move towards them. The courageous stewardship of kingdom values and ethics is central to evangelistic mission.

Trust is vital to relationship and mission. Our posture towards ethnic minority ministry is our posture towards the ethnic minority story. Trust is earned. The way it is earned amidst a history of power disparity is through a radical stewardship of power for the sake of others. This is a story straight from the pages of Scripture and the life of Jesus.

When we learn about the reality of others’ stories, we have choices to make about our own.

What kind of story do you want yours to be?

_______________________________

Brian graduated from UCLA and earned his MA in Transformational Leadership and MA of Divinity through Bethel Seminary. You can find him on Twitter at @BVirtue and at his web site http://brianvirtue.org

Eric, who writes under a pseudonym due to his involvement with Destino’s ministry among unreached peoples, graduated from Texas A&M and earned his MA in Cross Cultural Ministry at Dallas Theological Seminary. He blogs at destinoyearbook.com and you can find him on Twitter at @Destinoeric

Tommy graduated from UC Davis and is near completion of his degree in the Urban Lead MA of Divinity program at Biblical Seminary in Philadelphia. You can learn more at tommyandfatimah.com

All photographs © Jason Sorge Photography 2011. Jason is a former colleague of ours who has ministered through the Epic Movement. Find Jason on Twitter at @jasonsorge and at Jasonsorge.com

© brianvirtue.org, destinoyearbook.com, and tommyandfatimah.com 2011. You may use and reproduce this article in its current form as needed.

Click the thumbnail above to view this resource as a PDF.

Recent Comments