OUTCOMES

To have increased understanding of and language to describe the Asian American experience.

To see how each aspect of our Asian American stories points toward God’s redemptive mission.

WHY?

Where are you really from?

The sense of feeling like you belong, but not quite is all too familiar.

You’re Cambodian American, but you don’t speak the language.

You’re Korean American, but your family is white.

You’re Chinese American, but you’d rather use a fork than chopsticks.

You’re Indian American, but people don’t see you as Asian American.

How do we make sense of these realities? What are we to do as Christians with the complexities of the experiences that we and our families have as Asian Americans? How does God use this?

In Acts, we see Paul illustrate God’s purpose for each and every person’s story:

“And [God] made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place, that they should seek God, and perhaps feel their way toward him and find him. Yet he is actually not far from each of us.” (Acts 17:26-27, ESV)

The Asian American story is part of God’s larger narrative that includes the stories of every person, community, and ethnic group across all of time and every location. Acts 17 reminds us that God’s intent is that each aspect of these stories would contribute to leading people toward seeking and finding Him.

In this, each person’s story is unique and made up of multiple experiences woven together. It’s difficult trying to communicate those stories to others without losing the nuances that have shaped who we are. Like those moments when you have to translate for your parents. Or bringing food to school and being made fun of because they think your food stinks. Or those large family gatherings that never start on time and are filled with countless aunties and uncles and cousins – who you’re pretty sure are all related to you. And yet, God deeply cares for and knows each of these moments in our lives and wants to invite us into a deeper understanding of those experiences and of Himself.

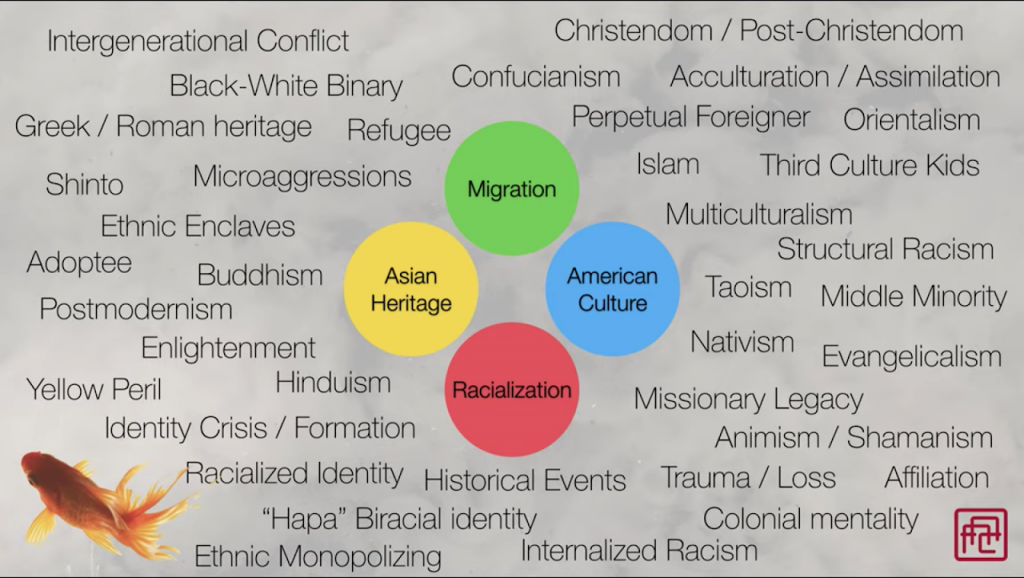

A helpful way to begin is by understanding the various parts of someone’s story through the lens of heritage, migration, dominant culture, and racialization. One story we can look at is Moses’s. God did incredible things through Moses by having Moses bring his own people out of slavery in Egypt and toward the Promised Land, but much of that part of his life didn’t begin until he was 80 years old.

His story began long before that. He was a tricultural man with a rich and complex heritage. A person residing temporarily in a place, migrating from one place to another – a sojourner. There are many details of his story that we often overlook. As we seek to gain awareness of how each detail is significant to the narrative of Moses’s life, read Acts 7:17-34 together to understand those first 80 years.

After reading Acts 7:17-34, go through and discuss the questions for each section: Heritage, Migration, Dominant Culture, and Racialization.

As God has “made from one man every nation of mankind” (Acts 17:26), He has created people and families of every ethnicity, tribe, tongue, and nation to live across the earth, each with a unique heritage. This heritage can include ethnic background, language, names, faith and religious beliefs, rituals and traditions, and more, which are inherited from their families.

Read

Exodus 2:6-10

Discuss Questions

- What is Moses’s heritage?

- Being raised by his birth mother, Moses was made aware of his heritage at an early age. How do you think that heritage influenced his life growing up in Egypt?

Although he grew up in Egypt, Moses was raised by his birth mother and it was through her that he learned about the stories and God of his ancestors (Acts 7:32), how to speak Hebrew, and what it meant to live as a Hebrew. Just as Moses was influenced by Hebrew culture, but grew up in Egypt, many Asian Americans are influenced by their Asian heritage, but grew up in the US. This Asian heritage is comprised of historical events, language, and beliefs and religions like Confucianism, Hinduism, Islam, or Buddhism.

In our lives, this could look like celebrating Tết (Lunar New Year), gesturing pagmamano, or honoring older generations. Each person will feel connected to this heritage in varying degrees, but it plays a significant role in influencing our lives and our faith. Indeed, our Asian heritage can reflect God’s beauty and creativity while also pointing to our brokenness and need for redemption.

Not only has God created people and families with particular cultural heritage, but He has “determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place” (Acts 17:26b) for them. This includes not only when and where people would reside at a given point in time but also how and why they and/or their families would move (or migrate) from one place to another.

Read

Acts 7:20-22, 27-34

Discuss Questions

- Where did Moses migrate to and from throughout his life? Under what circumstances?

- What/where do you think Moses considered home and how do you think that affected him?

Moses was a sojourner from birth, migrating from his birth family to an Egyptian home, to Midian, back to Egypt, and then eventually toward the Promised Land. Learning about someone’s migration experience is a way to understand how each family and person came to where they’re currently living. This can encompass immigrant, refugee, and adoptee experiences. From Toisan immigrants arriving at Angel Island to Hmong refugees being displaced to the Upper Midwest. From Filipino picture brides to the Vietnamese boat people.

Each story of migration traces back a deep history that explains part of our heritage and can oftentimes bring up mixed experiences of hopefulness, loss, and longing. In this, we are reminded of how God Himself sojourned on this earth so that we might become adopted as his children and live as exiles on this earth, longing for the hope of eternity.

As part of determining “the allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place” (Acts 17:26b), God also situates people within particular communities, societies, and nations. In each society, there is one culture which makes up the majority of people, becoming the dominant, influential culture. Sometimes people find themselves as part of that dominant culture, but often people find themselves as a minority, “a sojourner in a foreign land.” (Exodus 2:22b)

Read

Acts 7:22, 29

Discuss Questions

- What were the different dominant cultures Moses was surrounded by?

- How do you think Moses being a minority in the dominant culture affected him?

Moses found himself in the minority in Egypt and Midian, constantly learning a new culture and adapting to his current realities. For those of us who grew up in the US, majority culture is the western American culture that we are surrounded by and are currently living in. Some of these influences are the values placed on independence, the American church culture, and even the way Asian Americans have been represented in media. Depending on your community, this impacts each person differently on a daily basis. Growing in awareness of this can help give us a more holistic view of God and how He often chooses to use ethnic minorities in the accomplishment of His redemptive mission.

We see that God has created people and families with unique ethnic heritage, with particular migration stories, and within specific dominant cultures. But people inevitably begin to form assumptions (whether accurate or not) about themselves and others. Typically, these are based on physical and outward appearance, subsequently shaping how people and societies perceive themselves, others, and entire groups of people. These perceptions often result in sinful attitudes, actions, and systems such as prejudice, racism, and oppression.

Read

Acts 7:17-19

Discuss Question

- We see that Pharaoh “dealt shrewdly with [the Hebrew] race*…” (Acts 7:19). What are examples of how Moses and the Hebrew people were treated?

*in the NIV and other translations, “race” (genos, Greek) is translated in v.19 as “people”

Read

Acts 7:23-24

Hebrews 11:24-25

Discuss question

- How do you think these experiences could have affected how Moses saw himself and/or others?

Pharaoh oppressed the Hebrew people, and the reality is that Moses had the privilege of being able to ignore and benefit from their mistreatment. Despite that, Moses chose to leave his privilege and join the Hebrew people – his people – in their suffering. This brokenness also exists in our Asian American history, such as the racialization underpinning the Chinese Exclusion Act (1890) and the Japanese incarceration in “internment” camps (1942).

We see this today when others view us as a “perpetual foreigner” (“Where are you really from?”), assuming that we’re supposed to be the smartest kid in class, or playing a guessing game to determine our ethnicity. Or when we ourselves reinforce these stereotypes against other Asian Americans or other racial groups. These may seem harmless but can negatively impact how we see ourselves and others as we internalize these perceptions.

No matter, this dividing wall of hostility has no power over us in Christ. Just as Moses chose to be mistreated with the people of God, Jesus also enters into the mistreatment that Asian Americans face and at times perpetuate. Because of Jesus, “[we] are no longer strangers and aliens, but [we] are fellow citizens and members of the household of God.” (Ephesians 2:19). We are a part of God’s redeemed people and are invited to participate in His work of reconciling people to Himself and to one another.

Born as part of an enslaved Hebrew people with a rich cultural heritage, Moses was a Hebrew adoptee who was initially raised by his Hebrew birth mother but then grew up as adopted Egyptian royalty. He later renounced this privileged status, identified with the plight of his own oppressed people, killed an Egyptian, was rejected by both the Egyptians and Hebrews, and fled from Egypt to Midian as an exile. Marrying into a Midianite family, Moses lived in a foreign land before God called him to liberate the enslaved Hebrew people – that they might one day be able to enjoy God’s promises and blessings in the Promised Land.

Hebrew heritage, migration, Egyptian and Midianite culture, and racialization played crucial roles in Moses’s story. This is a Hebrew Egyptian who sojourned in Midian taking his place in God’s redemptive mission.

But what about us? Asian Americans taking our place in God’s redemptive mission can look like understanding how Asian heritage, migration, American culture, and racialization play influential roles in our stories.

Together, these four elements comprise an “Asian American Quadrilateral,” which can serve to help us to better understand and give language to our own stories and to the stories of others. This also provides avenues by which we can see God’s redemptive mission unfold in and through us, our communities, and our world. God is at work in each of our stories, that we “should seek God and perhaps feel [our] way toward him and find him [since] he is not far from each one of us” (Acts 17:27).

Asian American Quadrilateral – Dr. Daniel Lee

Recent Comments